Why std::expected matters for error handling

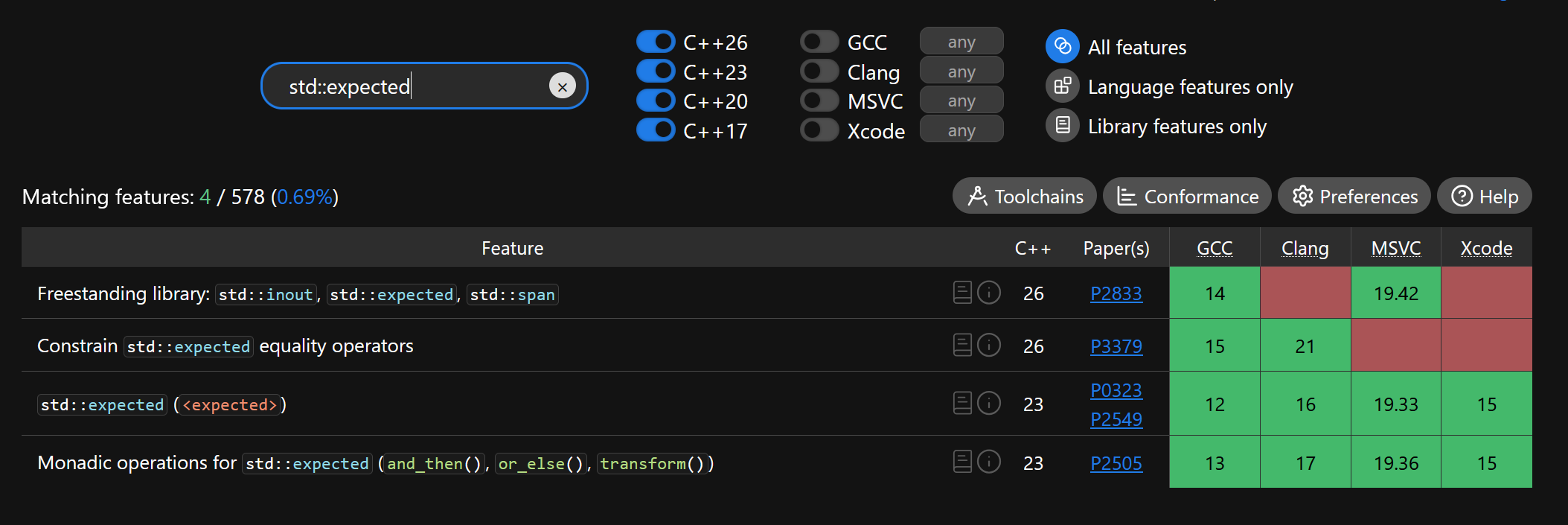

C++23 introduced std::expected, changing how we handle errors without exceptions. When you combine it with std::error_code (available since C++11), you get an error handling approach that forces explicit error checks while keeping your code readable.

The real power comes from std::error_code carrying more than just a number. Through std::error_category, it associates error codes with human-readable messages and std::error_condition values, letting you classify errors by severity (fatal, warning, informational) rather than checking individual error codes.

When to use std::expected

std::expected<T, E> shines when you need clear separation between success and failure:

- Type safety: The return value and error are distinct types. You can’t accidentally use an error as a valid result.

- Explicit checks: You must check for errors before accessing the value. No more forgetting to check return codes.

- Functional composition: Chain operations cleanly with

transform()andor_else():return readFile(path) .transform([](auto content) { return parse(content); }) .or_else([](auto error) { return handleError(error); });

When to combine it with std::error_code

std::error_code makes sense for non-throwing APIs where you need more context than a simple integer:

- No exceptions: Perfect for performance-critical code, embedded systems, or codebases with -fno-exceptions.

- Rich error context: Unlike

int VALUE_NOT_FOUND = 100, error codes come with categories and conditions. You can check if an error is “file-related” without knowing every possible file error code. - Cross-library consistency: Standard categories like

std::generic_category()andstd::system_category()work across different libraries.

The combination std::expected<T, std::error_code> gives you the best of both worlds—type-safe error handling with rich error information.

Why choose std::expected over std::error_code alone?

This is a common question, and the answer reveals the design philosophy behind C++ error handling.

std::error_code represents an error value, which typically is an integer code plus an error category. It’s powerful but requires discipline: you can accidentally ignore it, and the error is separate from your return value (often using output parameters or special sentinel values).

std::expected<T, E> takes a different approach. It’s a type-safe container that holds either a value or an error, never both, never neither. The compiler forces you to check which one you have before accessing the value. Think of it like Rust’s Result<T, E> or Haskell’s Either.

Here’s what sets them apart:

| Aspect | std::error_code | std::expected<T, E> |

|---|---|---|

| Type safety | Error separate from value; manual checks | Value and error bundled; compiler-enforced checks |

| Return style | Output parameters or sentinel values | Direct return type |

| Error propagation | Manual: if (ec) return ec; | Functional: .transform(), .or_else() |

| Forgetting to check | Possible—compiler won’t warn | Impossible—can’t access value without checking |

| Performance | Very cheap (integer + pointer) | Also cheap (no allocations, just a tagged union) |

| Best for | Legacy APIs, system integration | Modern APIs, composable code |

The best pattern? Use them together: std::expected<T, std::error_code>. You get type-safe control flow from std::expected plus standardized error reporting from std::error_code.

Practical examples

Traditional approach with std::error_code

Here’s the classic pattern—error code as return value, actual data as output parameter:

#include <fstream>

#include <filesystem>

#include <system_error>

std::string read_file(const std::filesystem::path& path, std::error_code& ec) {

std::ifstream file(path, std::ios::binary);

if (!file.is_open()) {

ec = std::make_error_code(std::errc::no_such_file_or_directory);

return {};

}

std::string content;

file.seekg(0, std::ios::end);

content.resize(file.tellg());

file.seekg(0, std::ios::beg);

if (!file.read(content.data(), content.size())) {

ec = std::make_error_code(std::errc::io_error);

return {};

}

ec.clear();

return content;

}

int main() {

std::error_code ec;

std::string contents = read_file("foo.txt", ec);

if (ec) {

std::cerr << "Error: " << ec.message() << "\n";

return 1;

}

// use contents...

}

This works, but notice:

- The function signature doesn’t clearly show what it returns

- You could forget to check

ecand usecontentsanyway - Output parameters make the API less composable

Modern approach with std::expected

The same functionality with std::expected is clearer:

#include <expected>

#include <fstream>

#include <string>

#include <system_error>

#include <filesystem>

#include <iostream>

std::expected<std::string, std::error_code>

read_file(const std::filesystem::path& path) {

std::ifstream file(path, std::ios::binary);

if (!file.is_open()) {

return std::unexpected(std::make_error_code(std::errc::no_such_file_or_directory));

}

std::string content;

file.seekg(0, std::ios::end);

content.resize(file.tellg());

file.seekg(0, std::ios::beg);

if (!file.read(content.data(), content.size())) {

return std::unexpected(std::make_error_code(std::errc::io_error));

}

return content;

}

int main() {

auto result = read_file("foo.txt");

if (!result) {

std::cerr << "Error: " << result.error().message() << "\n";

return 1;

}

std::cout << result.value();

}

Creating custom error categories with HTTP status codes

std::error_code becomes powerful when you define domain-specific categories. HTTP response codes are a perfect example—everyone knows what 404 or 500 means, but you still want to classify them generically (client error vs server error).

Here’s a real implementation for HTTP status codes:

// @file http_response_code.h

namespace network {

enum class http_response_code {

OK = 200,

CREATED = 201,

NO_CONTENT = 204,

BAD_REQUEST = 400,

UNAUTHORIZED = 401,

FORBIDDEN = 403,

NOT_FOUND = 404,

INTERNAL_SERVER_ERROR = 500,

SERVICE_UNAVAILABLE = 503,

// ... (complete list in actual code)

};

enum class http_error_condition {

INFORMATIONAL = 100,

SUCCESS = 200,

REDIRECT = 300,

CLIENT_ERROR = 400,

SERVER_ERROR = 500,

};

const std::error_category& http_error_category() noexcept;

}

// Register with the type system

namespace std {

template <>

struct is_error_code_enum<network::http_response_code> : std::true_type {};

template <>

struct is_error_condition_enum<network::http_error_condition> : std::true_type {};

inline std::error_code make_error_code(network::http_response_code code) noexcept {

return {static_cast<int>(code), network::http_error_category()};

}

inline std::error_condition make_error_condition(network::http_error_condition cond) noexcept {

return {static_cast<int>(cond), network::http_error_category()};

}

}

// @file http_response_code.cpp

namespace network {

class http_error_category final : public std::error_category {

public:

[[nodiscard]] const char* name() const noexcept override {

return "http";

}

// Error codes close to messages.

[[nodiscard]] std::string message(int ev) const override {

switch (static_cast<http_response_code>(ev)) {

case http_response_code::OK: return "OK";

case http_response_code::NOT_FOUND: return "Not Found";

case http_response_code::INTERNAL_SERVER_ERROR: return "Internal Server Error";

// ...

default: return "(unrecognized error)";

}

}

// std::error_condition classification

std::error_condition default_error_condition(int ev) const noexcept override {

const auto code = static_cast<http_response_code>(ev);

if (code >= http_response_code::OK && code < http_response_code(300))

return std::make_error_condition(http_error_condition::SUCCESS);

if (code >= http_response_code(400) && code < http_response_code(500))

return std::make_error_condition(http_error_condition::CLIENT_ERROR);

if (code >= http_response_code(500))

return std::make_error_condition(http_error_condition::SERVER_ERROR);

return std::error_condition(ev, *this);

}

bool equivalent(const std::error_code& code, int condition) const noexcept override {

return *this == code.category() &&

static_cast<int>(default_error_condition(code.value()).value()) == condition;

}

bool equivalent(int code, const std::error_condition& condition) const noexcept override {

return default_error_condition(code) == condition;

}

};

const std::error_category& http_error_category() noexcept {

static http_error_category instance;

return instance;

}

}

Now you can use it elegantly:

class http_response {

public:

std::error_code code{};

std::string body{};

[[nodiscard]] bool success() const noexcept {

return code == std::make_error_condition(http_error_condition::SUCCESS);

}

};

// Usage

auto response = http_client.get("https://api.example.com/users");

// Check specific code

if (response.code == http_response_code::NOT_FOUND) {

std::cerr << "Resource not found\n";

}

// Or check generic condition - this is the power of error_condition

if (response.code == http_error_condition::CLIENT_ERROR) {

// Handles 400, 401, 403, 404, etc. without checking each one

std::cerr << "Client error: " << response.code.message() << "\n";

}

if (response.code == http_error_condition::SERVER_ERROR) {

// Handles 500, 503, etc.

retry_request();

}

The beauty here: you can check for broad categories (CLIENT_ERROR) without knowing every specific code. This is what makes std::error_condition valuable—it carries the semantic weight of error classification.

Chaining operations functionally

One of the biggest advantages of std::expected is composability. You can chain operations without nested if-statements. Here’s a real-world example from XML parsing:

// Get a child element by name

std::expected<XmlElement*, std::error_code>

get_child_element(XmlElement* parent, std::string_view name) {

auto child = parent->first_child_element(name.data());

if (!child)

return std::unexpected(xml_errc::node_not_found);

return child;

}

// Extract text from an element

std::expected<std::string, std::error_code>

get_element_text(const XmlElement* element) {

const char* text = element->get_text();

if (!text)

return std::unexpected(xml_errc::node_empty);

return std::string(text);

}

// Extract integer from an element

std::expected<int, std::error_code>

get_element_int(const XmlElement* element) {

int value = 0;

if (!element->query_int_text(&value))

return std::unexpected(xml_errc::parse_error);

return value;

}

// Compose them with error handling

template <class T>

auto get_element_value(XmlElement* parent, std::string_view name) {

if constexpr (std::is_same_v<T, int>) {

return get_child_element(parent, name)

.or_else(log_parse_error(name))

.and_then(get_element_int);

} else {

return get_child_element(parent, name)

.or_else(log_parse_error(name))

.and_then(get_element_text);

}

}

// Usage - clean and error-safe

auto name = get_element_value<std::string>(root, "username");

auto age = get_element_value<int>(root, "age");

if (name && age) {

process_user(name.value(), age.value());

} else {

// Errors already logged via or_else

return std::unexpected(xml_errc::invalid_user_data);

}

This is similar to Rust’s ? operator or functional programming’s monadic composition. Each step automatically propagates errors, and .or_else() lets you handle errors inline without breaking the chain. No nested if-statements, no manual error propagation—the type system handles it.

Lessons learned

After working with both std::error_code and std::expected in production code, here are the key takeaways:

Do:

- Use

std::expected<T, std::error_code>for new APIs—it’s self-documenting and safe - Create custom error categories for domain-specific errors

- Map custom errors to standard conditions via

default_error_condition() - Leverage functional composition with

.and_then(),.transform(), and.or_else()

Don’t:

- Mix error handling styles in the same API boundary (exceptions + error codes + expected)

- Forget that

result.value()throws if the expected contains an error—usehas_value()first or usevalue_or() - Create too many error categories—group related errors under one category

Performance notes:

- Both

std::error_codeandstd::expectedare zero-cost abstractions std::expecteduses a tagged union internally—no heap allocations- Error message strings are only generated when you call

.message(), not on construction

Migration path: If you’re converting an existing codebase:

- Start by wrapping

std::error_codeinstd::expectedat API boundaries - Gradually convert internal functions to return

std::expecteddirectly - Keep error categories consistent across old and new code

A critical gotcha: error categories must be in shared libraries

This is important and non-obvious: error category definitions must be in a compiled translation unit (.cpp file), not header-only. If you define your category in a header that gets included in multiple translation units, error comparisons will break.

Why? The standard library’s error_category equality comparison uses pointer identity, not value comparison:

// Inside std::error_category

bool operator==(const error_category& rhs) const noexcept {

return this == &rhs; // Pointer comparison!

}

If your category is defined in a header, each translation unit gets its own instance. The pointers differ, so comparisons fail—even though they represent the same category.

The fix: Always define your category instance in a .cpp file and return it by reference:

// http_response_code.cpp - NOT in the header!

namespace network {

class http_error_category final : public std::error_category { /* ... */ };

const std::error_category& http_error_category() noexcept {

static http_error_category instance; // Single instance

return instance;

}

}

Then in your header, only declare the function:

// http_response_code.h

namespace network {

const std::error_category& http_error_category() noexcept;

}

This ensures every translation unit uses the same category instance, making pointer comparisons work correctly. This requirement ties error categories to compiled libraries—you can’t easily use them in header-only libraries without workarounds.

Conclusion

The combination of std::expected and std::error_code gives you the best of both worlds: type-safe APIs with rich, standardized error information. std::error_condition adds semantic weight by letting you classify errors generically (like HTTP’s client vs server errors) without checking individual codes.

It’s the current C++ way to handle errors without exceptions—just watch out for that category definition gotcha

The combination of std::expected and std::error_code gives you the best of both worlds: type-safe APIs with rich, standardized error information. It’s the current C++ way to handle errors without exceptions.